Each of Canada’s ten provinces regulates gender medicine differently. This gives each province the ability to adapt to new evidence more quickly and respond to the demands of local citizens better than if health care were centralized with the federal government. But this also means that it is harder to understand all the nuances of each system and to collect data from across the country. Over the coming months, we will do our best to profile the data and policies on medical transitioning for minors in each province.

Newfoundland and Labrador is unique. It was the last province to join Canada (in 1949), has its own special time zone (30 minutes ahead of the rest of Atlantic Canada), and boasts the most distinctive accent in the country. The population of the entire province is smaller than the city of Hamilton, Surrey, or Quebec City. It is the least densely populated province in Canada, and just under half of the population resides in or around St. John’s.

Unfortunately, Newfoundland and Labrador is not unique when it comes to sex-denying medicine. While it does not perform sex-denying surgeries due to its size and lack of facilities, the province has not tapped the brakes on medical transitioning for minors.

Policy

Newfoundland and Labrador’s Medical Care Plan (MCP) generally covers the cost of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones. The public health system also covers the cost of most sex-denying surgeries, but not all (e.g. facial feminization or voice pitch surgery).

Notably, all of the province’s policies and procedures relating to medical transitioning are based on the seventh version of WPATH’s Standards of Care (released in 2012) rather than the eighth version (released in 2022). The older edition notes that only 6-23% of cases of gender dysphoria in prepubertal children persisted into adulthood. Thus, “in most children, gender dysphoria will disappear before or early in puberty.”

Given this reality, the Standards of Care 7 are a bit more cautious about “gender-affirming care.” They recommend that clinicians working with gender dysphoric children and adolescents provide “supportive psychotherapy to assist children and adolescents with exploring their gender identity, alleviating distress related to their gender dysphoria.” But the Standards still support sex-denying procedures.

The seventh edition of the Standards of Care requires four criteria to be satisfied for clinicians to provide puberty blockers:

- The adolescent has demonstrated a long-lasting and intense pattern of gender nonconformity or gender dysphoria;

- Gender dysphoria emerged or worsened with the onset of puberty;

- Any co-existing psychological, medical, or social problems that could interfere with treatment have been addressed;

- The adolescent has given informed consent and, particularly when the adolescent has not reached the age of medical consent, the parents or other caretakers or guardians have consented to the treatment.

The Standards give no requirements for cross-sex hormones for minors specifically, though the following criteria are for hormone therapy in general:

- Persistent, well-documented gender dysphoria;

- Capacity to make a fully informed decision and to consent for treatment;

- Age of majority in a given country (if younger, follow the Standards of Care outlined in section VI [on children and youth]);

- If significant medical or mental health concerns are present, they must be reasonably well-controlled.

Curiously, although the third criterion refers to the section on children and youth, the section provides no further guidance on the prescription of cross-sex hormones to minors.

The Standards of Care 7 recommend that genital surgery not be performed prior to the age of majority, but suggests doing mastectomies earlier, “preferably after ample time of living in the desired gender role and after one year of testosterone treatment.” The requirements for surgery are the same as for cross-sex hormones, with the additional requirements of “12 continuous months of hormone therapy as appropriate to the patient’s gender goals (unless the patient has a medical contraindication or is otherwise unable or unwilling to take hormones)” for all genital surgeries and a further requirement of “12 continuous months of living in a gender role that is congruent with their gender identity” for genital reconstruction surgeries.

Thus, these requirements mandate no hard age limits on medical transitioning for minors, with the exception that bottom surgery is not recommended before the age of majority.

Providers

Trans Support NL, a non-profit organization that receives government funding, states that most gender-affirming care in the province is provided by a small group of providers that are mostly based in the St. John’s area. In response, the province is working to train primary care providers to provide gender-affirming care themselves. On its medical transitioning page, Trans Support NL encourages anyone seeking hormone replacement therapy to contact their family doctor.

However, there is one pediatric Gender Wellness Clinic at the Janeway Children’s Health and Rehabilitation Centre in St. John’s. The clinic serves children and youth under the age of 18 and is staffed by pediatric endocrinologists who prescribe puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones.

According to WPATH’s Standards of Care 7, only health care providers who meet “WPATH credentials” may provide surgical readiness assessments. Trans Support NL’s website lists four doctors who provide such assessments, though they note that the list is not exhaustive. Previously, the province had required a referral from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto for surgery.

The province does not perform most gender surgeries within the province. Most “top” surgeries are performed in New Brunswick, while most genital surgeries are performed at GRS Montreal.

Prevalence

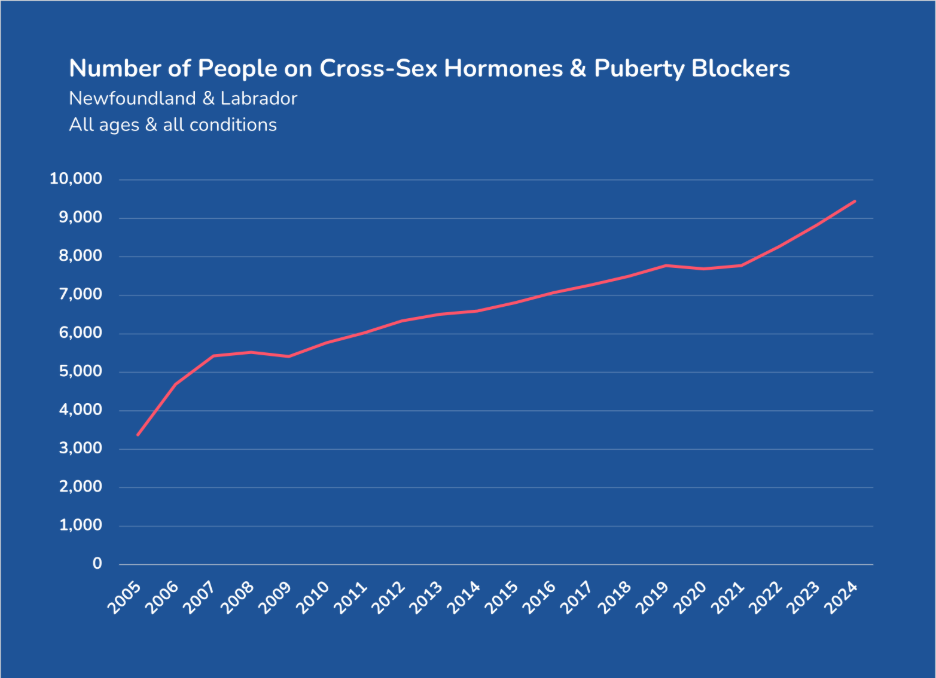

In response to an access to information request, the government of Newfoundland and Labrador did not have any records detailing the number of minors who had received sex-denying interventions. The province was able to release data on the number of patients of all ages receiving puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones, but only for all underlying conditions (e.g. precocious puberty, breast or prostate cancer, menopause, or naturally low hormone levels in addition to a medical transition).

Given this level of aggregation, it is impossible to deduce the number of children, adolescents, or even adults who are hormonally transitioning. However, the use of these drugs has nearly tripled in two decades. More minors who are medically transitioning may be one factor driving that growth, but we cannot know for certain.

The only surgical data that Newfoundland & Labrador released was that it approved 169 sex-denying mastectomies between November 2019 and May 2022. Only 22 of these mastectomies were actually performed, however. One reason for this discrepancy could be that some women and girls reconsidered having their breasts permanently removed. The more likely reason is that, since no facility regularly performs these surgeries, most gender dysphoric women and girls have not (yet) travelled to have a mastectomy. The province provided no information regarding the age of the patients for whom mastectomies were approved or performed.

Conclusion

Although there are no legal restrictions on medical transitioning for minors in Newfoundland & Labrador, the province does rely on the older – and slightly more stringent – WPATH Standards of Care 7. These standards permit puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and top surgeries for minors, though they recommend bottom surgeries only after the age of majority. All of these procedures are eligible for public funding. No data on the number of minors who are medically transitioning is available.

And so, while Newfoundland & Labrador might be unique, they are not unique in their liberal provision of medical transitioning.

Each of Canada’s ten provinces regulates gender medicine differently. This gives each province the ability to adapt to new evidence more quickly and respond to the demands of local citizens better than if health care were centralized with the federal government. But this also means that it is harder to understand all the nuances of each system and to collect data from across the country. Over the coming months, we will do our best to profile the data and policies on medical transitioning for minors in each province.

Prince Edward Island is the setting for a renowned children’s story: Anne of Green Gables. In the classic tale, an imaginative, talkative, and red-haired orphan is adopted by the Cuthberts. Anne initially struggles to fit in and bucks traditional norms. Accidentally dying her hair green doesn’t help. But through growth, love, and self-sacrifice, Anne eventually settles down and gives up her educational dreams to care for her adoptive mother. These themes reflect the values and times of 1908, the date Anne of Green Gables was published.

Many girls have similar struggles about fitting into today’s society. One of those growing struggles is over what it means to be a female or whether it is even possible to define what a woman or a girl is. A girl pushing back against gendered expectations (e.g. perhaps purposely dying her hair green) today might be drawn in by trans influencers, contract gender dysphoria, and pursue a medical transition to find belonging and identity.

Sadly, rather than encouraging a modern Anne to allow time and biology to take their course, Prince Edward Island would be all too willing to help Anne medically transition.

Policy

According to PEI’s Primary Care Toolkit, the Consent to Treatment and Health Care Directives Act allows minors over the age of 16 to consent to sex-denying hormones without parental consent. No minimum ages are required or recommended for puberty suppression or hormone therapy, though states of puberty are mentioned. Puberty suppression is recommended in “the early stages of puberty” and hormone therapy for those “past puberty or well-advanced in puberty.” As with all other provinces, PEI covers the cost of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones.

Prince Edward Island publicly funds more forms of sex-denying surgeries than any other province. In addition to paying for all forms of genital surgeries as well as both mastectomies and breast augmentations, the province will also pay for procedures that other provinces deem cosmetic or non-medically necessary. This includes facial surgery, hair removal or replacement therapy, voice therapy, and gamete harvesting and preservation.

For the province to cover the cost of these surgeries, physicians or mental health professionals who are trained in “gender-affirming care” (as defined by WPATH’s SOC 8) must assess the patient, recommend surgery, and complete a Gender Confirming Surgery Prior Approval Request Form. This form requires applicants for surgery to affirm that they are at least 18 years old. A physician must also attest to this age requirement for genital surgery further on. This seems to rule out sex-denying surgeries for minors. However, the Primary Care Toolkit notes that “there may be rare exceptions for those who began their transitions at a young age.”

Providers

The government’s Gender-Affirming Health Services page offers two different routes for a medical transition for minors. Minors under the age of 16 are directed to a pediatrician to discuss any medical transition. Those over the age of 16 are encouraged to contact their primary health provider. These pediatricians and family doctors can prescribe sex-denying hormone therapy. Alternatively, these mature minors can visit the Gender Affirming Clinic in Charlottetown, a clinic that is open on the first and third Wednesdays of each month.

Due to the province’s small population, most sex-denying surgeries are not performed on the island. Most are performed at GrS Montreal except for hysterectomies (removal of the uterus) and oophorectomies (removal of the ovaries), which are performed locally.

Prevalence

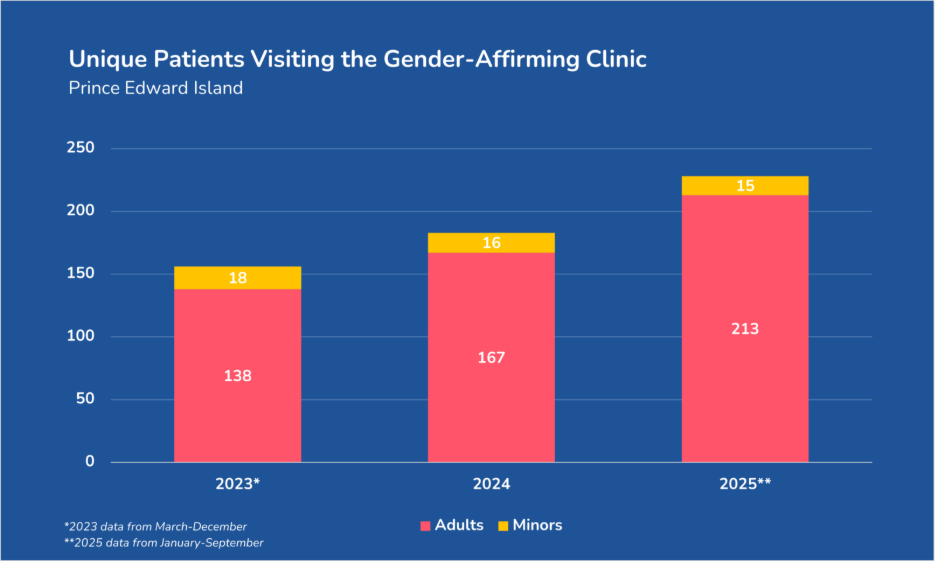

In response to our access to information request, Prince Edward Island did not have any data on the number of people who visited a primary care provider for gender dysphoria or the number of patients currently prescribed puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones. The province was only able to release the number of patient visits and the number of unique patients to the province’s one Gender-Affirming Clinic. This data covered only the last three years and does not capture all of 2023 nor all of 2025.

In each of these (partial) years, the majority of patients were adults. Despite the steady growth in the number of adults visiting the clinic, the number of minors has remained relatively stable over the past three years. At least eighteen minors visited the Gender-Affirming Clinic in the last 10 months of 2023, although a couple more may have dropped in January and February that year. Sixteen visited in 2024. Fifteen visited through the first nine months of 2025, but by the end of the year, that total will likely be a few visitors higher.

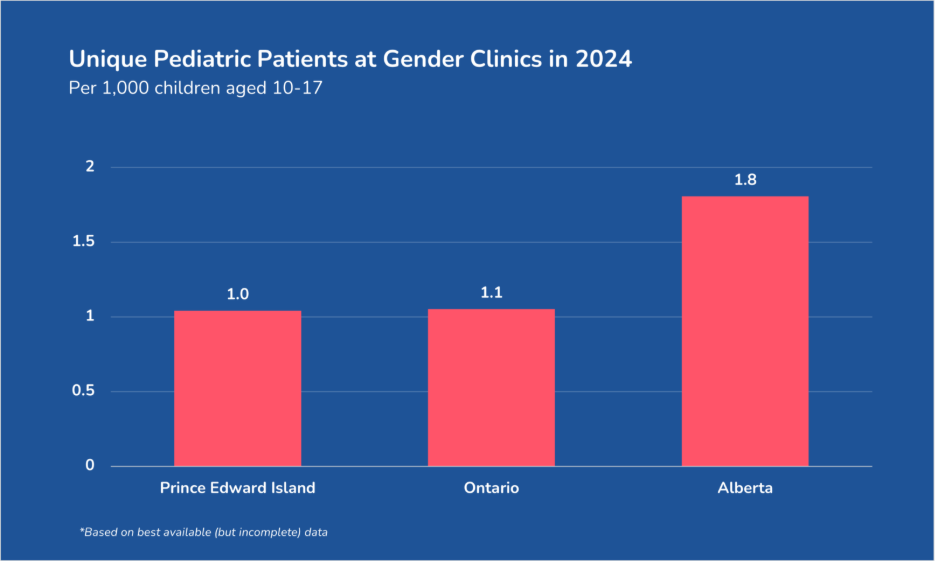

These numbers may be small, but that is because Prince Edward Island has a small population of around 182,000. (For comparison, the entire population of the island is comparable to the mid-sized cities of Sherbrook, Oshawa, or Abbotsford.) Thus far in this series, we have data on the number of unique pediatric visitors to the Gender-Affirming Clinic in Prince Edward Island, the hospital-based gender clinics in Ontario, and the hospital-based gender clinics in Alberta. If we compare the number of children and adolescents who visited these with the number of children and adolescents in each of these provinces, the rates of minors seeking help with their gender dysphoria are comparable. In Prince Edward Island, there are 1.0 pediatric gender clinic visits per 1,000 children aged 10-17. In Ontario, that rate was 1.1. In Alberta, it was 1.8. While this data is incomplete (e.g. it does not take into account community gender clinics in Ontario or Alberta), this gives us some idea of the rate at which children and adolescents are seeking help with gender dysphoria.

The province reports that fewer than five sex-denying procedures have been performed in the province in the last 25 years. Given that all other surgeries are performed out of province, these surgeries were likely hysterectomies and oophorectomies. All of these surgeries were performed on adults. No sex-denying surgeries have been performed in minors in PEI.

Conclusion

Despite its small size and population, Prince Edward Island is not immune to the promotion of medical transitioning. It fully funds more types of sex-denying procedures than any province in the country. Although gender surgeries are limited to adults, there are no age restrictions on hormonal interventions. Most children suffering from gender dysphoria are referred to pediatricians or family doctors, though there is one dedicated gender clinic in Charlottetown. Forty-nine minors have visited this clinic in the last three years, but the number of minors who have been treated for gender dysphoria by family doctors is unknown. The number of children and adolescents who are on puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones is also unknown. Thankfully, there is no record of any underage Prince Edward Islander ever receiving a sex-denying surgery.

With nearly 40% of Canada’s population, Ontario likely provides the greatest number of medical transitions to minors in the country. While the Ontario policy and providers of sex-rejecting interventions are publicly available, any specific statistics on the number of children and adolescents who are transitioning are lacking.

Until now.

After describing Ontario’s gender medicine policies and where these interventions are provided, this article gives some insight into the extent of medical transitioning for minors in Canada’s largest province.

Policy

As with most other Canadian provinces, Ontario doesn’t regulate medical transitioning. Sherbourne Health, an organization that provides services “to people who may experience barriers to accessing health care” such as “2SLGBTQ people” runs Rainbow Health Ontario. Rainbow Health Ontario is the province’s leading promoter of medical gender transitioning. As part of their efforts, Rainbow Health Ontario publishes its own 136-page Guidelines for Gender-Affirming Primary Care with Trans and Non-Binary Patientsto help clinicians in their day-to-day practice. However, the document focuses on those who have completed puberty “and does not address considerations for trans and non-binary children or youth who have not completed puberty.”

The Guidelines promote an “informed consent model” for hormonal transitions rather than a traditional “gatekeeper model.” This informed consent model dispenses with any in-depth mental health assessment or referral process, though the Guidelines claim that this does not equal “hormones on demand.” Sherbourne Health claims that “new patients are usually seen for a number of visits prior to the initiation of hormone therapy,” though urgent cases are fast-tracked. A diagnosis of gender dysphoria or gender congruence is recommended prior to hormonal transition.

To be eligible for public funding under OHIP, a physician or nurse practitioner must fill out a Request for Prior Approval for Funding of Sex-Reassignment Surgery to be approved by the Ministry of Health. This form requires that a patient be assessed “by a provider trained in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of gender dysphoria in accordance with the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care.” This assessment for “chest surgery” requires the diagnosis of persistent gender dysphoria for a mastectomy and a gender dysphoria diagnosis plus 12 months of continuous hormone therapy with no resulting breast enlargement (unless hormones are not recommended) for breast augmentation. For “genital surgery,” the assessment requires a diagnosis of persistent gender dysphoria, 12 continuous months of hormone therapy (unless hormones are not recommended), and 12 continuous months of living in their new gender role.

These are not legal requirements, however. They are funding requirements. It is perfectly legal to perform a sex-denying surgery on a minor who doesn’t have a diagnosis of gender dysphoria, who has never been on cross-sex hormones, or lived in their “new gender role.” Those requirements must only be met if the surgeon or patient wants the government to pay for their surgical transition.

Ontario covers the cost of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and most “top” and “bottom” gender surgeries for minors if the proper forms are submitted. Some chest contouring and breast augmentation procedures are not publicly funded.

Providers

Puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones are relatively easy to access in Ontario. Many primary care providers (i.e. family doctors) now prescribe them to children and adolescents. One study with data collected in 2009-10 found that 67% of trans-identifying people in Ontario who were hormonally transitioning were prescribed these hormones by their family doctor. Rainbow Health Ontario believes that percentage “is almost certainly greater now.”

But if a family doesn’t have a family doctor who is willing to prescribe hormones, many community health clinics offer them. For example, Northern Ontario’s Gender Diversity Clinic, York’s Gender Affirming Health Clinic, Kingston’s Transgender Health Program, Durham’s Gender Care Team, Chatham-Kent’s Youth Gender Diversity Clinic, and Thrive Kids’ Clinic’s Gender-Affirming Pediatric Care program in Toronto all explicitly say on their websites that they prescribe puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to children and adolescents.

There are also four hospital-based gender clinics in Ontario. SickKids Hospital Gender Clinic in Toronto, “one of the largest transgender youth clinics in Canada,” and CHEO’s Gender Diversity Clinic in Ottawa garner the most attention. But the London Children’s Hospital’s Gender Pathways Service and McMaster Children’s Hospital Adolescent Medicine Clinic provide hormonal transitioning to children as well.

Gender surgeries are primarily performed at the Women’s College Hospital in Toronto and the Ottawa Hospital. The Women’s College Hospital began offering gender surgeries in 2018, claiming to be the “first public hospital-based surgical program in Canada focused on providing safe and timely access to gender affirming surgical care.” It offers most “top” and “bottom” surgeries. The Ottawa Hospital’s gender-affirming surgery clinic opened in 2023, offering not only “top” and “bottom” surgeries but also facial feminization and masculinization surgeries. That hospital claims that “it is the only clinic in Ontario and the second in Canada to offer all three” types of procedures.

Specialty clinics such as Catalyst Surgical and GraceMed are dedicated to exclusively providing gender surgeries, with GraceMed alone claiming to have performed over 2,500 gender surgeries since 1988. Other plastic surgeons and clinics across the province also list “gender-affirming surgeries” among their wider cosmetic offerings.

Prevalence

It is challenging to find data on the number of minors who are medically transitioning in Ontario. The ideal dataset would reveal the full number of minors currently prescribed puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones for the purpose of a gender transition, plus the number of “gender-affirming” top and bottom surgeries performed on minors each year. But there are a couple of factors that make such data difficult to collect.

First, so many players are involved in gender medicine – children’s hospitals, specialized gender clinics, and family doctors. Not everyone involved in providing gender medicine is reporting all the needed data. And so, the little data available is often only a few puzzle pieces of the entire picture. Second, because all the medications or surgeries prescribed for a gender transition are also used to treat other conditions (e.g. precocious puberty, breast or prostate cancer, menopause, or naturally low hormone levels), it is difficult to isolate prescriptions for “gender-affirming care.” For example, it is relatively straightforward to find the number of prescriptions of testosterone through a public drug plan. But that data isn’t very helpful when the reason for prescribing testosterone isn’t listed in the data.

Because of all of this, the government doesn’t publish comprehensive data on medical transitioning anywhere. In most cases, that’s because the government doesn’t have the information. They simply let the system of medical transitioning carry on.

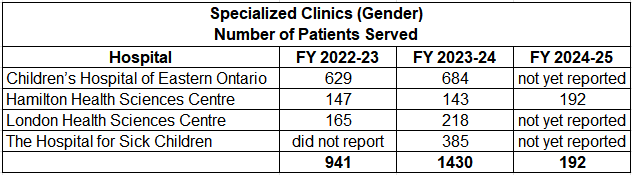

A couple of FOI requests to the government of Ontario confirm this. The government confirmed that they do not comprehensively track the number of minors receiving puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones at community health clinics from family doctors. However, the Ministry of Health began receiving data on the number of children and adolescents served at the four hospital-based gender programs. Due to a lack of reporting, the only total that we can report with certainty is that these hospital-based pediatric gender clinics saw 1,430 children in 2023-24. The Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) in Ottawa saw more than half of those patients. And in three of the four comparative years, the number of minors visiting these clinics increased from the previous year.

These numbers, however, are just the tip of the iceberg. They do not include the number of children and adolescents seen at community gender clinics or by family doctors. Remember that as far back as 2009-2010, two-thirds of hormonal transitions were prescribed by family doctors, and that figure is likely much higher today. If family doctors still see two-thirds of all children with gender dysphoria and community gender clinics see as many children as the hospital-based clinics, the number of children seeking medical help for gender dysphoria would be approximately 8500 a couple of years ago.

Furthermore, Ontario stated that it does “not track SRS [sex reassignment surgeries] performed in-province.” Ironically, they do track such surgeries performed out-of-province and even out-of-country.

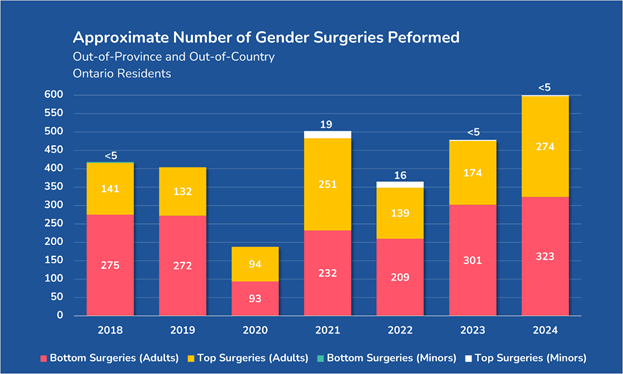

From 2018-2024, Ontario sent almost 3,000 individuals out of the province and even out of the country for gender surgeries. That averages out to about 420 per year. For the sake of context, Ontario sent more residents out of the province for gender surgeries than the province of Alberta performed last year. Now, Ontario doesn’t send patients out of the province for these surgeries because no institution provides them in Ontario. As mentioned above, hospitals and gender surgery clinics provide the full gamut of gender surgeries in the province. Patients were likely sent out of the province and out of the country because there was too much demand for these surgeries for these Ontario hospitals and clinics to handle. Sending patients outside Ontario allowed them to get surgery faster.

The government did not release the locations of where these surgeries occurred, but most out-of-province surgeries likely occurred at GrS Montreal, which is well known for handling gender surgeries for people around Canada.

Relatively few gender surgeries (roughly 40) were performed on minors out-of-province or out-of-country over the last few years. In 2018, fewer than five minors were sent out of the country for a phalloplasty. (Ontario lists numbers between one and four as <5, which makes data less precise but protects individuals’ privacy.) Nineteen minors received mastectomies out of province in 2021, sixteen more in 2022, and fewer than five in both 2023 and 2024.

Many gender ideologues claim that gender surgeries are not performed on minors in Ontario. But the above data demonstrates that minors from Ontario have been operated on out of province, paid for by OHIP. And while there is ironically no data on gender surgeries performed within Ontario (even though we have data on out-of-province surgeries for Ontarians), with no legal or clinical rules against it in Ontario, such surgeries have likely happened here too.

Conclusion

There are no legal restrictions on medical transitioning for minors in Ontario. The non-governmental organization Rainbow Health Ontario provides guidelines for clinicians, but its guidelines don’t address age restrictions. Puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and most “top” and “bottom” surgeries are eligible for public funding through OHIP, provided that a person is diagnosed with persistent gender dysphoria. In some cases, a twelve-month waiting period is required as well.

Unfortunately, only some of the data on children who are medically transitioning is available. Over 1,400 children visited hospital-based gender clinics in 2023-24. Many more visited community gender clinics or their family doctor. Approximately 40 minors received mastectomies out-of-province in the last few years, and up to four minors received bottom surgeries out-of-country in 2018. No data is available on the number of gender surgeries performed in the province.

Under the Microscope: Nova Scotia

Each of Canada’s ten provinces regulates gender medicine differently. This gives each province the ability to adapt to new evidence more quickly and respond to the demands of local citizens better than if health care were centralized with the federal government. But this also means that it is harder to understand all the nuances of each system and to collect data from across the country. Over the coming months, we will do our best to profile the data and policies on medical transitioning for minors in each province.

Policy

Nova Scotia is the only province other than Alberta to have clearly stated age restrictions for medical transitioning in its Gender Affirming Care Policy. Unfortunately, it only applies to surgery. The general rule is that a person must be 18+ to receive gender transition surgery, but 16- and 17-year-olds may request an exemption if they “demonstrate the emotional and cognitive maturity required to provide informed consent.” In other words, there are exceptions to this rule for mature minors.

However, Nova Scotia’s policy sets no hard age limits on hormonal therapies (puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones). Instead, following the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care (SoC) 8, Nova Scotia requires that a gender dysphoric adolescent must have begun puberty (i.e. Tanner 2). The policy states that adolescents normally reach this stage of development between the ages of 8-14 years.

Most forms of medical transitioning are publicly funded. Hormonal therapies are covered under the Nova Scotia Pharmacare Programs. “Top” and “bottom” surgeries are also publicly funded through the province’s Medical Services Insurance, though other surgeries (e.g. facial feminization, liposuction, tracheal shave and voice pitch surgery) are not covered.

Providers

The primary provider of pediatric gender medicine is IWK Health, formerly the Izaak Walton Killam Hospital for Children. According to their website, “IWK Health is a proud leader in gender-affirming care. We ensure youth in Nova Scotia access support and treatment based on evidence. Gender-affirming services at IWK Health include assessment for gender incongruence and assisting non-binary and transgender adolescents in understanding and meeting their embodiment and health goals.”

Nova Scotia Health advises that adolescents 17 and younger living within the Halifax Regional Municipality will be served by IWK Health’s Trans Health Team, while those outside the area will be connected with a “trans health clinician” in a local Community Health Centre. Specialized gender youth clinics recently opened in Kentville and Bridgewater, with more such clinics in the works. Eighteen-year-olds (who are still minors in Nova Scotia) can simply go to their family doctor or nurse practitioner or to a “WPATH SoC-trained clinician.”

As for surgeries, while some are performed in Nova Scotia, the province sends most people seeking surgeries to the Centre Métropolitain de Chirurgie-GrS Montréal in Quebec.

Prevalence

As we’ve mentioned before, it is challenging to find data on the number of minors who are medically transitioning. The ideal dataset would reveal the full number of minors currently prescribed puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones for the purpose of a gender transition, plus the number of “gender-affirming” surgeries performed on minors each year. But there are a couple of factors that make such data difficult to collect.

First, so many players are involved in gender medicine – children’s hospitals, gender clinics, and family doctors – that it is hard to collect all the relevant data. Not everyone involved in providing gender medicine reports all of the needed data. And so, the little data available makes up only a few pieces of the puzzle. Second, because all the medications or surgeries prescribed for gender transition are also used to treat other conditions (e.g. precocious puberty, breast or prostate cancer, menopause, or naturally low hormone levels), it is difficult to isolate prescriptions for “gender-affirming care.” For example, it is relatively straightforward to find the number of prescriptions of testosterone through a public drug plan. But that data isn’t very helpful when the reason for prescribing testosterone isn’t listed in the data.

In sum, the government doesn’t publish comprehensive data on medical transitioning anywhere. In most cases, that’s because the government doesn’t have the information. They simply let the system of medical transitioning carry on.

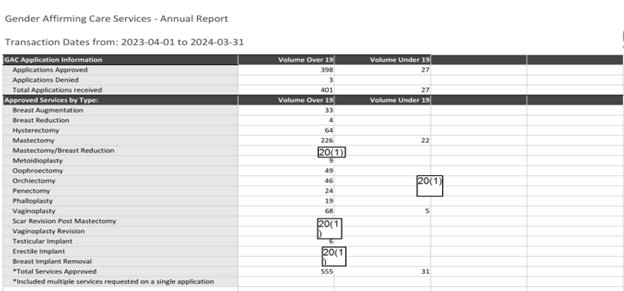

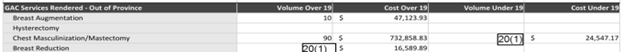

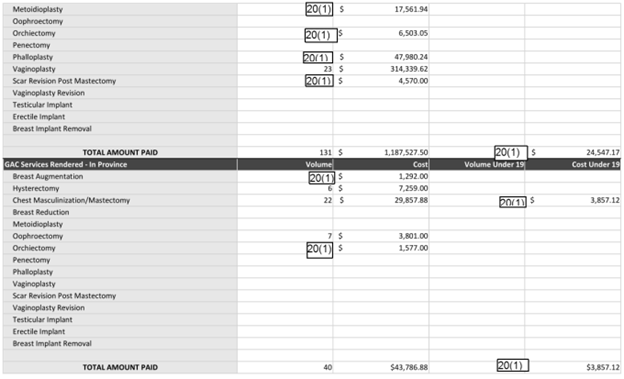

Some data on the number of minors who are medically transitioning in Nova Scotia have been uncovered by various Freedom of Information Requests, mostly filed by Melanie Bennet from Juno News. The FOIs revealed that 21 “top” surgeries (mastectomies) and 9 “bottom” surgeries were approved for minors in the fiscal year 2023-2024 in Nova Scotia and out of province. (In an attempt to maintain privacy, every number that is below 5 is redacted under the code 20(1). Hence, each cell obscured by 20(1) could be read as below 5 but at least 1.)

However, only a few of these surgeries were actually performed. No “bottom” surgeries and fewer than five “top” surgeries were performed on Nova Scotians younger than 19 from 2023-2024.

The reason for the difference between the number of surgeries approved and performed is not clear. It is possible that there was enough of a time delay between the approval of a gender surgery and the performance of a gender surgery that the person aged out of the data. For example, an 18-year-old could be approved for a mastectomy, but that mastectomy isn’t performed until she is 19. Alternatively, a young person may initially want surgery and receive approval but then decide they don’t want it.

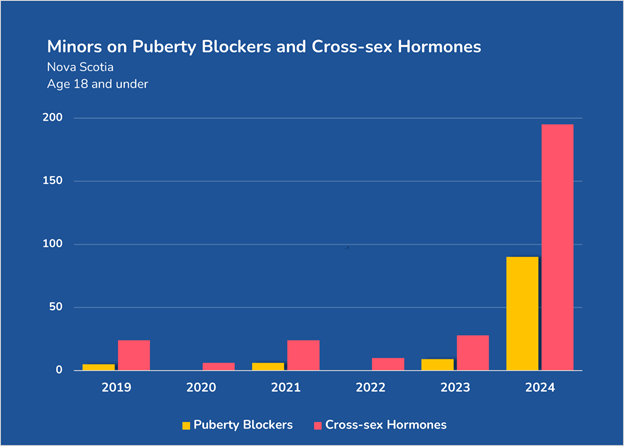

Unlike most other provinces, Nova Scotia has released some data on the number of minors receiving puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones in recent years. Prescriptions for these hormonal interventions were relatively low from 2019-2023, with no more than 9 minors receiving puberty blockers and 37 receiving cross-sex hormones in a given year. But these numbers exploded in 2024 when 90 received puberty blockers and 195 received cross-sex hormones the following year. That is a 1000% and 696% increase, respectively, in a single year.

The reason for this spike is unclear. It may be the result of the opening of a new youth gender clinic in Kentville in February of 2024, allowing many minors who wanted hormones but previously couldn’t get them to access them. Or the number of minors actually seeking gender hormones went up drastically. Neither of these seems plausible to account for such a dramatic spike, however. It might simply be due to differences in data reporting, with the majority of minors receiving hormone therapy not being reported in previous years.

Conclusion

As in most other provinces, Nova Scotia liberally permits medical transitioning for minors. There are no hard and fast age restrictions to receive puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones. The province generally restricts “top” and “bottom” surgeries to those eighteen and older, but allows exceptions to this policy for 16- and 17-year-olds. Unlike most other provinces, Nova Scotia has some specific data on the number of minors who are medically transitioning. Ninety kids were prescribed puberty blockers and 285 were prescribed cross-sex hormones in 2024. Twenty-two were approved for “top” surgery and nine for “bottom” surgery in 2023-2024, though fewer than five actually received a mastectomy, and none received genital surgery.

Alberta has led the country in limiting medical transitioning for minors. And just last week, Alberta took another unprecedented step to protect the health and well-being of children: invoking the notwithstanding clause.

Early in 2024, Premier Danielle Smith announced that Alberta would take steps to restrict these interventions, which until then had no legal age restrictions. Her government’s Bill 26, the Health Statutes Amendment Act, contained provisions to ban “puberty suppression,” “hormone replacement therapy,” and “sex reassignment surgery” to treat gender dysphoria or gender incongruence for any minor under the age of 18.

Alberta took another unprecedented step to protect the health and well-being of children: invoking the notwithstanding clause.

Despite the legislation’s passage in late 2024, only the ban on surgeries is in force right now. The government has not brought into force the provisions that ban “hormone therapies.” The rationale for this delay was the promise to craft an exception to allow “minors aged 16 and 17 with parental, physician and psychologist approval” and “minors who have already been prescribed hormone replacement therapies” to receive these pharmaceuticals. Such an exception has yet to be drafted, with no explanation for the year-long delay. The government could have brought the law into force, but, for whatever reason, has not chosen to do so.

While the provincial government inexplicitly delayed, a new barrier arose that prevented the law from taking effect. This summer, Justice Allison G. Kuntz issued a preliminary injunction to prevent the ban on puberty blockers from coming into force, claiming that the law might infringe on Charter rights.

The government is already in the process of appealing this injunction, paving the way for the full ban on medical transitioning for minors to go into effect. But that legal process could take years, years in which hundreds of children and adolescents could be prescribed a medical transition.

And so, to bypass this potentially lengthy legal procedure, the government invoked the notwithstanding clause with Bill 9, the Protecting Alberta’s Children Statutes Amendment Act. The notwithstanding clause is a clause in the Canadian constitution that allows the elected parliament or legislature (rather than the courts) to be the final arbiter of whether a law violates certain sections of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. With the ban on medical transitioning for minors shielded by the notwithstanding clause, the opinion of the courts remains just that: an opinion. Thus, a law could remain in effect despite a contrary opinion of the courts.

Once considered the nuclear option to resolve differences between courts and legislatures, this provision is experiencing a renaissance (outside of Quebec, which has a long history of using the clause). Ontario used the notwithstanding clause to amend election spending rules. Saskatchewan invoked the section to pre-empt legal challenges to its legislation requiring parental consent for their children’s attempt to change their name or pronouns at school. The federal Conservatives have repeatedly promised to use it to ensure that criminals are appropriately punished. And just last month, the Alberta government relied upon the notwithstanding clause to end a teacher’s strike.

The notwithstanding clause allows the elected parliament or legislature (rather than the courts) to be the final arbiter of whether a law violates certain sections of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

This is precisely what is needed to safeguard the health of young people and prevent these radical interventions. We know that over 1600 minors have visited Alberta’s two main pediatric gender clinics in the last five years. And we know that 36 minors have had gender surgeries over the past decade. Hundreds of children each year are being prescribed gender medicine.

This even though over 80% of cases of pre-pubescent gender dysphoria among children resolve naturally after puberty. When clinicians cannot tell with any certainty whether a young person will persist or desist in their gender dysphoria, the responsible option is to wait and see, rather than turning to medical interventions that prevent development or surgically remove healthy organs.

Rather than being cautious, clinicians in Canada are often far too quick to refer gender dysphoric children to the progression of medical transitioning. According to one study, over 62% of children and young adolescents referred to gender clinics in Canada were provided with hormones on the very first visit. Rather than providing kids time to think, taking puberty blockers sets children on the path of a further medical transition. As many as 98% of minors who take puberty blockers go on to take cross-sex hormones.

And while pro-transition advocates claim that these interventions are “medically necessary” to protect the health, well-being, and even the life of “gender diverse” young people, the evidence to back that claim up is sparse at best. The United Kingdom’s Cass Review and the United States’ Health and Human Services Review find that there is little to no high-quality or long-term evidence to support the benefits of medical transitioning for minors. Earlier this year, two Canadian studies found the same thing.

Alberta is taking the right step in invoking the notwithstanding clause to ensure that its restrictions on medical transitioning for minors go into effect.

For all of these reasons, Alberta is taking the right step in invoking the notwithstanding clause to ensure that its restrictions on medical transitioning for minors go into effect. Alberta is doing the hard part. But they need to do the easy part too. They need to proclaim the sections of the law that ban the provision of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones.

Without these actions, the law is just a façade. It looks impressive, but it isn’t functional. Alberta needs to finish the job of banning medical transitioning for minors. Invoking the notwithstanding clause is one step towards that goal, but more remains to be done.

Dr. Gordon Guyatt is no lightweight. Inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame in 2016, Guyatt is one of Canada’s most cited researchers with over 1,200 publications, which have been cited by other scholars at least 100,000 times.

Guyatt is most known for his contributions to evidence-based medicine. In fact, he coined that very term. Evidence-based medicine is “one of the great innovations in general medical practice over the last several decades.” As its name implies, the goal of evidence-based medicine is to make medical decisions based on scientific evidence. This might seem to be an obvious goal (e.g. what would medicine be based on if not evidence?). But the novelty of evidence-based medicine was to apply the most rigorous standards to assess existing evidence and then make medical recommendations.

Guyatt was also an architect of one specific tool of evidence-based medicine: the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). GRADE assesses the degree of certainty of academic studies and how various factors increase the certainty or uncertainty of the study’s findings. For example, GRADE will assess whether studies are biased towards certain findings. Evidence of bias reduces the certainty of a study’s findings.

“The goal of evidence-based medicine is to make medical decisions based on scientific evidence.”

Evidence-based medicine and GRADE have become the gold standard in science. In a world with so much information available, so many different study methodologies, and so much politicization in academics, evidence-based medicine helps medical practitioners to make the best medical decisions.

Evidence-based medicine and medical gender transitions

This GRADE methodology was briefly mentioned in the United Kingdom’s Cass Review and extensively used in the United States’ Treatment for Pediatric Gender Dysphoria: Review of Evidence and Best Practices. Both of these seminal reviews strongly recommended against medical transitioning for minors. But relatively little work has been done in Canada.

So, Guyatt and a team of researchers from McMaster University decided to apply evidence-based medicine and GRADE to assess the academic literature on medical gender transitions. The Canadian team of researchers wrote two papers, applying GRADE methodology to review studies on the effect of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormone therapy on youth under the age of 26.

The results confirmed earlier reviews. They found that there was very low certainty about the effects of giving puberty blockers to children and adolescents with gender dysphoria on global function (i.e. overall well-being), depression, gender dysphoria, bone mineral density, and likelihood to progress to receive “gender-affirming hormone therapy.” The authors noted that all the studies suffered from methodological issues such as high risk of bias and imprecision. This study “is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the effects of puberty blockers in children, adolescents and young adults with GD [gender dysphoria] using the highest methodological standards.”

Guyatt’s team’s analysis of cross-sex hormones did not fare much better. The researchers had very low certainty about the effects of giving cross-sex hormones to children, adolescents, and young adults regarding their global function, depression, gender dysphoria, sexual dysfunction, and bone mineral density. The only finding that the researchers were highly certain of was that taking cross-sex hormones increased the risk of cardiovascular events (e.g. heart attacks or strokes) within 7-109 months.

“Here we have two more studies that we can pile onto the growing list of academic papers that caution against medical transitioning for minors.”

Notably, the two studies used the age cut-off of 26. Most studies, medical systems, and legal codes focus on children and adolescents under the age of majority (usually 18 or 19). But the Finnish guidelines, commentary on the Swedish guidelines, and the Cass Review on medical transitioning for minors have noted that the human brain isn’t fully developed until age 25.

Yet children, youth, and young adults are currently allowed to make irreversible decisions about their bodies before their brain is fully developed. Puberty blockers affect the development of their brain. Some of their impacts might not be fully apparent until brain development ends. Given these realities, it makes sense not only to assess the impact of a medical transition, not just on children and adolescents up to 18 or 19, but on young adults up to 26 as well.

Here we have two more studies that we can pile onto the growing list of academic papers that caution against medical transitioning for minors.

But that’s not the end of the story.

Evidence meets ideology

In the months after publishing these two studies, Dr. Guyatt was condemned by trans activists for publishing the study. They didn’t like an academic paper that failed to wholeheartedly support medical transitioning. Under pressure, Guyatt, his fellow researchers, and McMaster published a letter saying that “We are concerned our findings will be used to justify denying care such as puberty blockers and hormone replacement therapy to TGD individuals… it is unconscionable to forbid clinicians from delivering gender-affirming care… forbidding delivery of gender-affirming care and limiting medical management options on the basis of low certainty evidence is a clear violation of the principles of evidence-based shared decision-making and is unconscionable.”

Well, it is only unconscionable if patient autonomy is far more important than evidence. The entire practice of “gender-affirming care” is predicated on the idea that puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgeries are beneficial treatments for gender dysphoria. Guyatt’s studies find that there is very low certainty that these benefits exist. If that is true, then medical transitioning can hardly be “medically necessary.” Actually, it can’t reasonably be called “health care” if there is very low certainty that it improves health. Trans advocates often speak about “embodiment goals,” using puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, or surgeries to achieve a certain appearance. Interventions for these reasons certainly aren’t a form of health care. They are cosmetic interventions.

“Guyatt’s studies find that there is very low certainty that these benefits exist.”

As part of their penance for their ideological sins, the researchers “personally made a donation to Egale Canada’s legal and justice work, noting their litigation efforts aimed at preventing the denial of medically necessary care for gender-diverse youth”. Egale Canada is a pro-trans group that, among other things, launched a legal challenge of Alberta’s restrictions on medical transitioning for minors. So the champions of a bias-detecting tool like GRADE made very public donations to an activist group. Not a great fit.

To further complicate the story, Guyatt later said that he strongly disagreed with EGALE’s stated view that medical transitioning is “medically necessary care for gender-diverse youth.” Yet that statement was made in a letter that Guyatt signed. When asked about why he signed a letter he didn’t agree with, Guyatt responded that he must not have read the 507-word letter carefully enough before signing it.

Dr. Guyatt may be a Medical-Hall-of-Famer, but that’s a rookie mistake.

Evidence-based and ethical medicine

Evidence can’t exist in a value-free vacuum. We are convinced that medical transitioning for minors isn’t a value-free activity either. The prevalence of harm, the question of consent, the rush to transition, and the immutability of sex all justify efforts by governments to curtail the practice. When studies find little certainty that medical transitioning improves the health and well-being of those suffering from gender dysphoria, greater caution over these interventions must be exercised.

On Wednesday, October 8th, British Columbia became the second province to introduce a bill to ban medical transitioning for minors. However, while such a ban was proposed and then passed by the governing party in Alberta, the Protecting Minors From Gender Transition Act was introduced by a member of the fourth party in the BC Legislature, MLA Tara Armstrong of OneBC.

Here is how she introduced the bill:

Members, I stand before you today not only as a member at this Legislature but as a mother. British Columbia is sleepwalking through the greatest medical scandal in modern history, and it’s our kids who are at risk. In B.C. today, doctors are causing irreversible harm to children with puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones and surgeries. These interventions rob children of the human right to grow up with their bodies intact and to one day have children of their own. B.C. schools add to this harm by socially transitioning children with new names and pronouns, often kept secret from parents. Gender clinics in B.C. are even performing double mastectomies on healthy young girls by the age of 14. All because we fell for the lie — a lot of us did — that children can be born in the wrong body. It’s not true though. Every child is beautiful just as they are. No drugs or scalpels are needed. Every jurisdiction in the world that has conducted a systematic review of the scientific literature has found no credible evidence to support this practice. So let’s all make it stop. This should not be a partisan issue. This bill will bring B.C. in line with the U.K. and other progressive European countries that have banned harmful and unscientific social and medical gender transition procedures for minors. In our schools, it will stop them using the wrong pronouns, keep boys out of girls’ bathrooms and remove gender ideology from school libraries and curriculum. It will stop doctors from attempting to change the sex of minors. In short, it will end this unbelievable era of indoctrination and medical malpractice. Please join me as we restore sanity to this province and provide the loving care that every child deserves.

It was a great speech. But sadly, the Protecting Minors From Gender Transition Act didn’t even make it past first reading in the legislature. MLAs voted 48-40 that the bill not pass first reading, meaning MLAs did not even have the opportunity to read the contents of bill before defeating it. This is very unusual but not unprecedented. Last year, the BC legislature did the same thing when BC Conservative leader John Rustad introduced a bill on segregating publicly funded sports by sex.

In both cases, the majority of MLAs were so captured by gender ideology that they refused to even read bills that question gender ideology, much less have a substantial discussion about it in the legislature.

More than just a ban on medical transitioning

MLA Armstrong’s bill would have gone further than any legislation in Canada in removing gender ideology from medicine and from education.

It would have defined “male,” “female,” and “sex” as based on biology rather than being arbitrarily assigned at birth or based on a person’s subjective belief. It defined gender as “the psychological, behavioural, social, and cultural aspects of being male or female.” In other words, the bill views gender as being the outworking of our biological differences.

The bill would have banned all forms of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and gender surgeries aimed at addressing “the minor’s perception that his gender or sex is not male/female.” This would have gone further than Alberta’s recent legislation, in part because Alberta’s age of majority is a year earlier (18 in Alberta, 19 in BC). But Alberta’s legislation only prohibits puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones for ages 15 and under but permits 16- and 17-year-olds to access puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones with parental, physician, and psychologist approval. Alberta’s law has no restrictions past age 17.

The Protecting Minors From Gender Transition Act proposed heavy penalties for medical transitioning minors, including “suspension of the healthcare professional’s ability to administer healthcare or practice medicine for at least one year.” Furthermore, the bill would have made any medical professional who provided medical transitioning to a child liable for any physical, psychological and emotional harm to the child caused by the medical transition for the next 25 years. The bill also would have prevented professional liability insurance from covering this liability, shifting the risk entirely to health care providers and providing another deterrent.

Additionally, the bill would have prohibited the use of public funds, property, or time to pay for or promote medical transitioning for minors. This would exclude the provincial Medical Services Plan or BC PharmaCare Plan from covering the cost of these procedures or guidance on government websites on where minors could undergo medical transitioning in another province.

But the bill wasn’t just about medical transitioning. It also dealt with gender ideology and social transitioning in schools. The legislation would have required school employees to notify parents within three days if their child wishes to socially transition. School staff would have been forbidden to use pronouns that are inconsistent with a student’s sex, regardless of parental notification or consent. This goes a step further than Alberta’s and Saskatchewan’s laws that permit the use of pronouns based on gender identity with parental consent.

Further on the school front, the bill would have required schools to prohibit students from using an opposite-sex restroom, locker room, or changing facility. School staff would not be permitted to use any material or offer any program that encouraged or normalized a social transition or a medical transition. Whether this clause would entirely ban SOGI teaching resources, pride paraphernalia, or gay-straight alliance clubs is unclear.

Finally, the bill invoked the notwithstanding clause to shield it against the courts striking it down as a violation of The Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Opponents of Alberta’s ban on medical transitioning for minors have used the Charter to challenge Alberta’s law. While some of these legal cases are still underway, an Alberta judge did grant a preliminary injunction preventing the ban on puberty blockers from going into effect, as she opined that it might violate the Charter.

This is not the end

The introduction of this bill gives cause for hope in the cause of banning medical transitioning for minors, despite its quick demise. It shows how the desire to limit these harmful interventions isn’t just limited to Alberta but is present elsewhere in Canada. It shows that these objections aren’t just limited to private citizens or on social media but shared by politicians who are willing to raise this issue in the legislature. And it shows that, despite the defeat of the bill, many MLAs are willing to vote to ban the practice. The legislation failed in a relatively close vote, 48-40.

This legislation may be defeated in British Columbia for now, but the campaign to let kids be is only gaining momentum.

Image and audio source - The Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. (Oct 8, 2025). BC Legislature Livestream [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8KOX5oRWSo

Original article published Sep 23, 2025; updated on Sep 24, 2025 and Dec 12, 2025.

Each of Canada’s ten provinces practices gender medicine differently, as provinces have primary jurisdiction over health care. This gives each province the ability to adapt to new evidence more quickly and respond to the demands of its local citizens better than if health care were centralized with the federal government. But this also means that it is harder to understand all the nuances of each system and to collect data from across the country. Over the coming months, we will do our best to profile the data and policies on medical transitioning for minors in each province.

Our series is going to begin with Alberta.

Policy

Alberta is the lone province in the country that has taken the greatest steps to limit medical transitioning for minors. Prior to 2024, Alberta had no legal restrictions on the intervention, though “bottom” surgeries (e.g. penectomy, phalloplasty, vaginoplasty, orchiectomy) were rarely, if ever, performed on minors in practice. Pre-pubescent children received puberty blockers, and adolescents received cross-sex hormones and “top” surgeries without age restrictions.

That changed in late 2024 when the Alberta legislature passed Bill 26, the Health Statutes Amendment Act. The new law bans “puberty suppression,” “hormone replacement therapy,” and “sex reassignment surgery” to treat gender dysphoria or gender incongruence for any minor under the age of 18. (Eighteen is the age of majority in Alberta.) However, the law permits the Minister of Health to create exceptions for puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones through regulation. The government intends to use this clause to allow “minors aged 16 and 17 with parental, physician and psychologist approval” and “minors who have already been prescribed hormone replacement therapies to treat gender dysphoria or gender incongruence” to receive these pharmaceuticals.

Although the law passed the legislature, not all of these provisions banning medical transitioning are in force. In fact, only the ban on gender surgeries for those under 18 applies right now. The sections dealing with “hormone therapies” (i.e. puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones) will come into force upon Proclamation (when an order from Cabinet brings them into force). Ostensibly, the government is waiting to make this law legally binding until it has created the ministerial order that makes the exemption for 16- and 17-year-olds and minors already on puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones.

The bottom line? Alberta has banned surgical transitions for minors and set the stage to ban puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones for minors, but hasn’t implemented the full ban yet. Hormonal therapies for minors are still legal.

Providers

According to the Alberta Health Services’ hospital and facility directory, three main institutions in the province participate in pediatric gender medicine:

- University of Alberta Hospital’s The Gender Program in Edmonton – Stollery Children’s Transgender Clinic embedded within the University of Alberta Hospital

- Aberhart Centre’s Pediatric Endocrinology Clinic in Edmonton

But pediatric gender medicine is not just the purview of specialized gender clinics. It is increasingly being practiced by primary care providers, more commonly known as family doctors. Gender ideologues in medicine have taken up the slogan “gender-affirming care is primary care.” Another journal article opines that “because primary care providers often have in-depth understanding of their patients’ medical and mental health background and the greater context of their lives and support networks, they are well positioned to assess a patient’s readiness for gender-affirming hormone therapy and initiate treatment.”

According to one freedom of information request, the majority of physicians prescribing the hormones used in medical transition to minors are family physicians. Between 2019-2023, an average of 22 family physicians started minors on a medical transition each year, compared to an average of 10 pediatricians.

Prevalence

As we’ve mentioned before, it is challenging to find any data on the number of minors who are medically transitioning. The ideal dataset would list the entire number of minors currently prescribed puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones for the purpose of a gender transition, plus the number of “gender-affirming” top and bottom surgeries performed on minors. But there are several factors that make such data difficult to collect. First, so many players are involved in gender medicine – children’s hospitals, specialized gender clinics, and family doctors – that it is hard to collect all the data into one centralized spot. Every participant would have to report in order for the data to be complete. Second, because all of the medications prescribed for a gender transition are also used to treat other conditions (e.g. precocious puberty, breast or prostate cancer, menopause, or naturally low hormone levels), it is difficult to isolate just prescriptions for “gender-affirming care.” And finally, the involvement of both provincial drug programs and private insurance programs in funding “gender-affirming care” makes it difficult to track the money. Hence, governments don’t publish this data anywhere. In some cases, it doesn’t even seem like the government even has the information. They simply let the system of medical transitioning carry on.

The government of Alberta put it this way:

Currently, there is no data system within Alberta that tracks the number of children receiving gender care. While administrative health care data systems such as Morbidity and Ambulatory Care Abstract Reporting (MACAR), Supplemental Enhanced Service Event (SESE), and Pharmaceutical Information Network (PIN) provide some insights into aspects of gender care (breast surgeries, genital surgeries funded out-of-province, and hormone prescriptions) they do not directly capture the real figures for children receiving gender-related treatments. Consequently, the exact number of children in Alberta who are receiving gender care remains unknown.

Although comprehensive data is unavailable, health administrative records should have some information on the number of children and adolescents who are medically transitioning, and so we submitted several freedom of information requests to access any of the data that the government has.

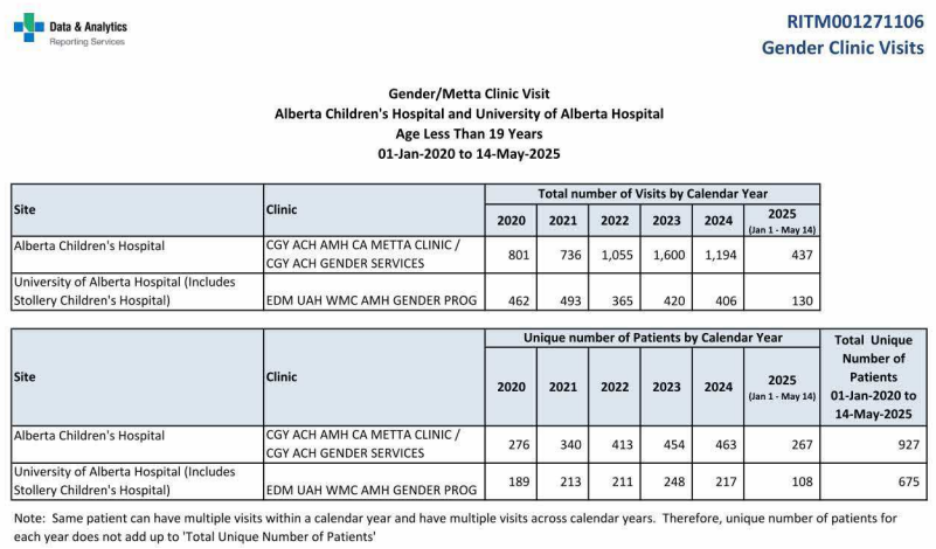

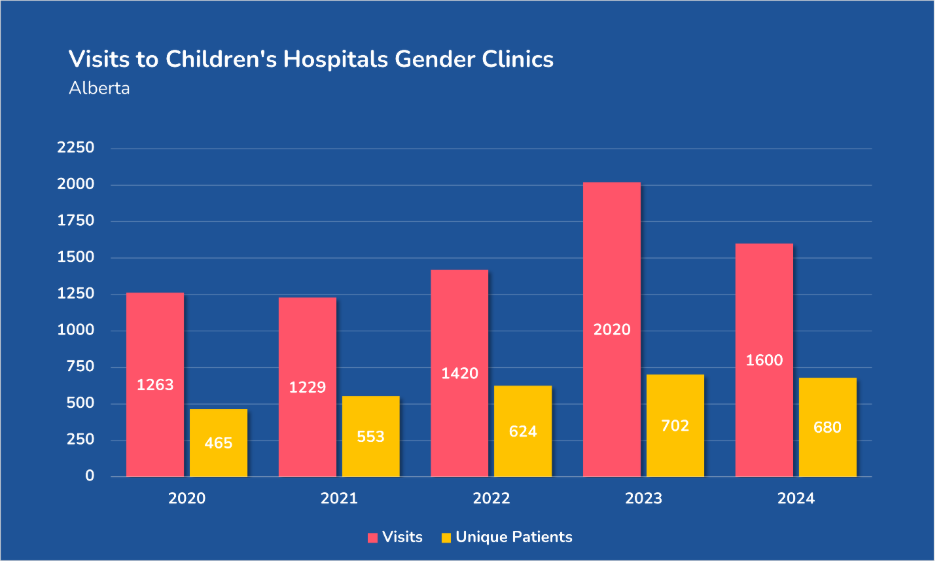

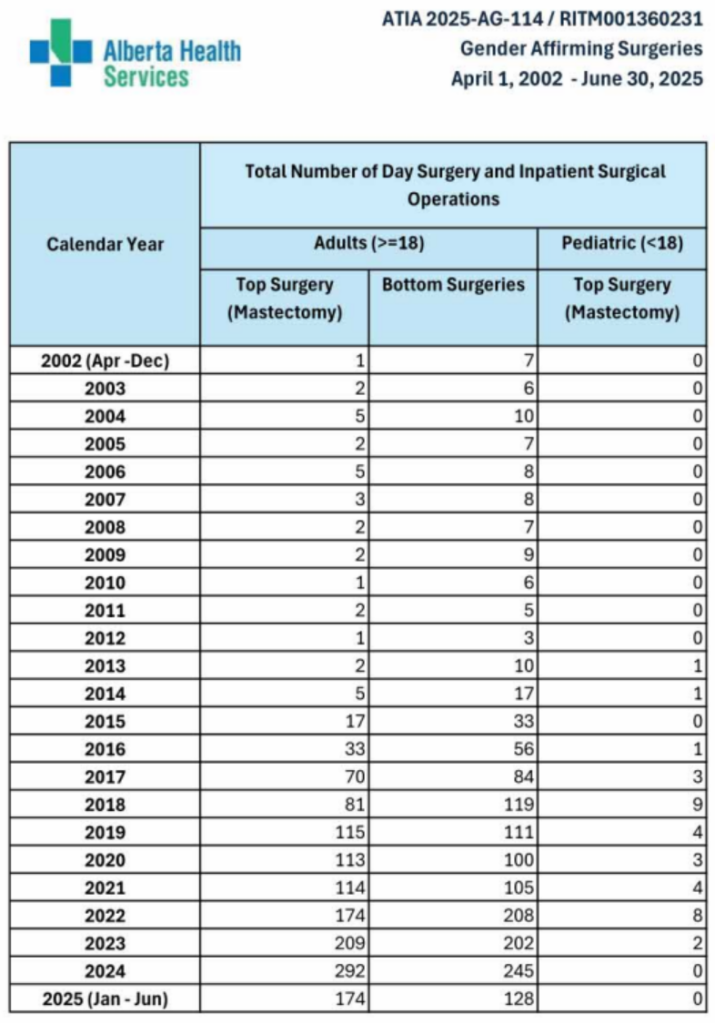

One FOI request was for the number of patients seen at Alberta’s two main gender clinics at Alberta Children’s Hospital and Stollery Children’s Hospital between 2000-2025. The government released the following data.

The first thing to note is that this data records the number of unique patients and total visits to these two gender clinics for whatever reason. Now, not all children struggling with their gender identity and visiting a gender clinic choose to medically transition. What this data does show is the number of children and adolescents struggling with gender dysphoria and considering – if not obtaining – a medical transition.

And these numbers have been growing over the past few years. The number of visits reached 2,020 in 2023, while the number of unique patients peaked at 702 in 2024.

And this isn’t even everyone. It accounts for those visiting Alberta’s two largest pediatric gender clinics, but it doesn’t include those visiting the Aberhart Centre’s Pediatric Endocrinology Clinic or lesser-known pediatric gender clinics, nor those who received puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones from family doctors. What we can say with some certainty is that at least 1,600 minors have sought to medically transition in the last five and a half years in Alberta.

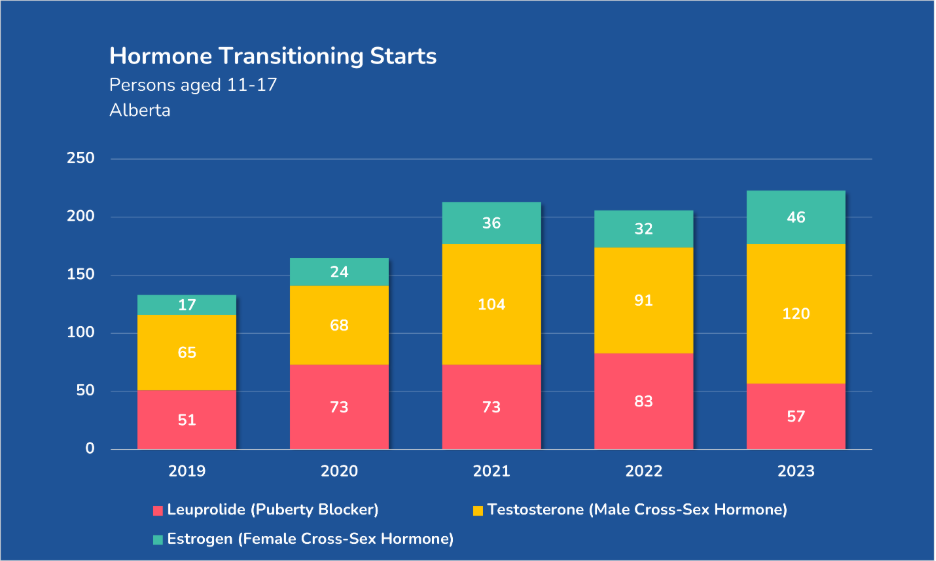

Another FOI sheds more light on the actual number of children hormonally transitioning. Taken from the Pharmaceutical Information Network (PIN), this data records the number of first pharmacy dispenses for gender care starts for persons aged 11-17. In other words, it tells us how many adolescents begin medically transitioning each year. It does not tell us cumulatively how many minors are medically transitioning in a given year.

This data shows a growth in the number of adolescents who are hormonally transitioning from 133 in 2019 to 223 in 2023. However, these numbers seem to have plateaued.

Thirty-six percent of hormonal transitions begin with puberty blockers, typically children in their pre-teens showing the first signs of puberty. Sixty-four percent start with cross-sex hormones, with those seeking a masculine transition outnumbering those seeking a feminine transition three to one.

Note that, in addition to the number of children visiting Alberta’s children’s hospitals, there are many more children visiting community gender clinics and family doctors. In other words, far more children are likely seeing medical professionals because of gender dysphoria than just those who end up at these children’s hospitals.

Thankfully, very few of them have received sex-denying surgeries. In another FOI, the government stated that “all lower or bottom surgeries are only available for people 18 years of age or older,” and so there were no recorded instances of a minor receiving these procedures. Thirty-six minors did receive “top surgeries” between 2013 and 2023, however, before the ban on such surgeries went into effect in 2024. And yet, at its height in 2018, one of every ten “gender-affirming” mastectomies was performed on minors.

Conclusion

Alberta may have taken the furthest steps toward banning medical transitioning for minors, but it is still far from that goal. Surgical transitioning for minors is banned. The legislature has enacted a ban on puberty blockers and hormone therapies, but the ban has not fully come into effect. At least two major health care institutions – Alberta Children’s Hospital and Stollery Children’s Hospital – are providing puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to minors. At least 1,600 minors have sought to medically transition at these two institutions alone in the last five and a half years in Alberta, though only about two hundred youth have newly begun to medically transition in each of those years in the entire province. Relatively few have had any sex-denying surgery.

If you live in Southern Ontario, you may have seen a billboard or bus ad like these in your local communities. Our goal with these billboards was to bring attention to the issue of medical transitioning for minors and garner support for the campaign to ban medical transitioning for minors.

And they’ve certainly gotten attention!

Everything started back in December when a local group collected money, negotiated a contract, and put up LetKidsBe.ca bus ads in the city of London. Those ads received a lot of attention from the media and from pro-transitioning groups. The London Free Press, CBC, and CTV covered the bus ads in some fashion, with a heavy bias against the ads and in favour of medical transitioning for minors.

The London Transit Commission (LTC), having previously lost a court challenge to the Association for Reformed Political Action (ARPA) Canada (the creator of LetKidsBe.ca), kept the ads up despite pressure to remove them. LTC Chair Stephanie Marentette said LTC could not reject the ad because doing so would violate freedom of expression. “Unless something is egregious or amounting to hate speech. that would trigger an exception. Unfortunately we don’t have the ability to arbitrate what types of ads go on the side of our buses. This is something we don’t have a lot of control over, the Supreme Court is the highest court in the country.”

But this action inspired more action.

A local group of Let Kids Be supporters in Hamilton wanted to see this message featured on a billboard on the Lincoln Alexander Parkway, a high-traffic expressway for commuters. Procuring such a prime location was an expensive endeavour, but they managed to raise the funds, and the electronic billboards in Hamilton went up on Monday, August 4th.

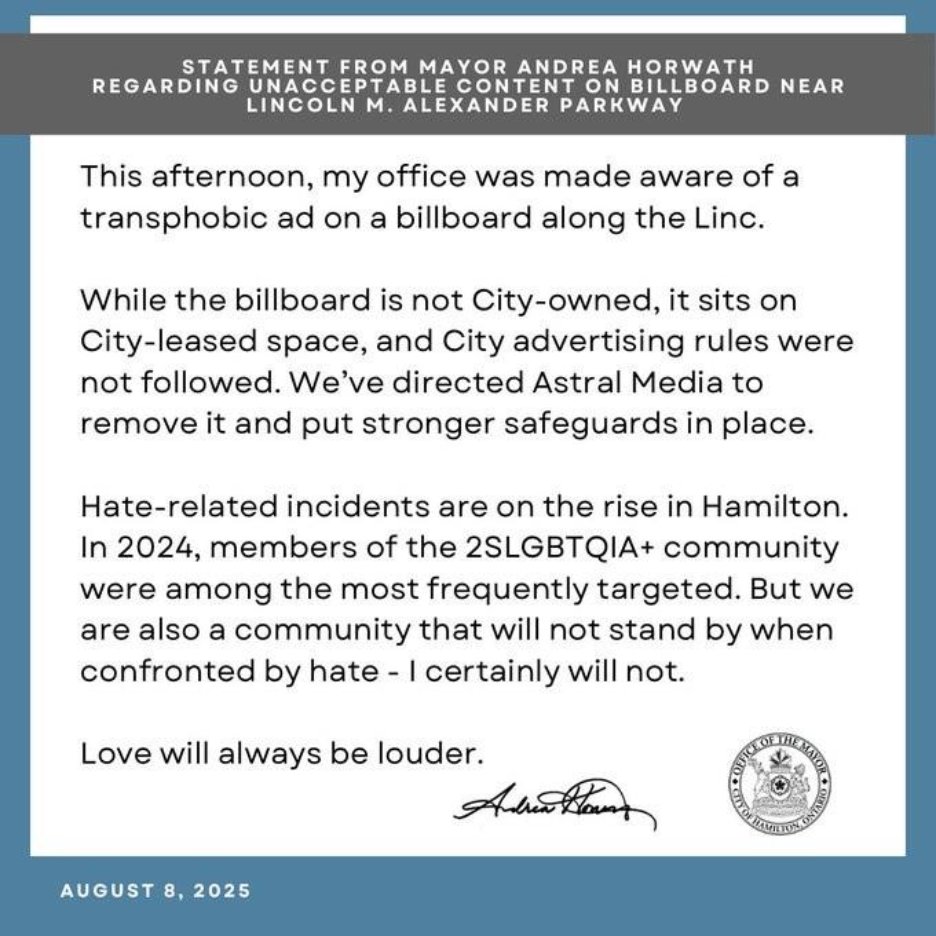

That Friday, August 8th, the Hamilton Trans Health Coalition posted a warning on Facebook about the billboard, labelling it “disinformation,” “a harmful message,” and “an attempt at this [anti-trans] politicization.” Late that evening, Hamilton mayor Andrea Horwath, the former leader of the Ontario NDP, posted the following message on X:

“This afternoon, my office was made aware of a transphobic ad on a billboard along the Linc.

While the billboard is not City-owned, it sits on City-leased space, and City advertising rules were not followed. We’ve directed Astral Media to remove it and put stronger safeguards in place.

Hate-related incidents are on the rise in Hamilton. In 2024, members of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community were among the most frequently targeted. But we are also a community that will not stand by when confronted by hate – I certainly will not.

Love will always be louder.”

Before the end of the day, Astral/Bell media took down the billboards.

Undeterred by this event in Hamilton, a group of Let Kids Be supporters in Niagara pressed on. After some investigation, they found an advertising company that had billboards on private land. Since putting up billboards on city-leased space enabled the City of Hamilton to get them taken down, they thought that placing a billboard on private land would ensure that it would remain up. They contacted Vann Advertising to erect three billboards. Two of the billboards were digital, located back-to-back along the QEW in St. Catharines, another high-traffic expressway. The third billboard, this one printed on vinyl, was in downtown St. Catharines.

The electronic billboards went up on Monday, August 25th, and the physical billboard was erected shortly thereafter.

The reaction was swift. Within days, the physical billboard was vandalized.

Pride Niagara called “on the City of St. Catharines to take urgent action against a transphobic billboard” and claimed that “this harmful and dehumanizing message spreads dangerous misinformation and creates an unsafe environment for trans and gender-diverse people in our community.” They encouraged people to reach out to Mayor Mat Siscoe and sent a letter to city hall themselves. Mayor Siscoe then called Vann Advertising, asking them to reconsider displaying the billboards. Furthermore, Vann Advertising received some aggressive messaging from LGBTQ activists. Worried about the viability of the company and its owners’ safety, Vann Advertising removed the billboards.

But that is not the end. A private billboard owner in Hamilton was willing to sell us digital billboard space in downtown Hamilton. More groups around the county are considering putting up Let Kids Be billboards in their local communities, and we are pursuing legal action to ensure that local governments do not violate the Charter right to the freedom of expression.

Ironically, the efforts of activists to censor these Let Kids Be ads have caused the call to stop medical transitioning for minors to reach far more people. Billboards are seen in passing only by those who happen to pass by them. But when they become the subject of a censorship battle which media reports on, their reach extends to many more people. People see the ad on their computers and phones, just a quick search away from the Let Kids Be website. And because our messaging is so clear, direct, and respectful, even media that are biased against us tend to report what the billboard said and often show the billboard itself. This respectful advocacy starkly contrasts with the disrespect shown by the other side when they vandalize a billboard.

So take heart. More and more Canadians are hearing the message that we need to stop medical transitioning for minors. If you or your local group want to sponsor a local Let Kids Be billboard, the graphics are available for you to use. The more billboards that go up, the more the message gets out!

But if you do participate in this endeavour, realize that erecting a billboard isn’t the end of the project. It is the beginning of a conversation. If a Let Kids Be billboard is up in your community, use that opportunity to encourage the billboard company to keep up the ad. Urge your local politicians to not interfere with private advertising. Petition your MPP/MLA and your MP to take action to ban medical transitioning for minors.

Sex-based violence against women and girls – violence perpetrated against females solely because they are females – is a sad reality of our world. To combat this injustice, the United Nations established a Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls in 1994. The mandate of the current Special Rapporteur, Reem Alsalem, is not only to identify common forms of violence against women and girls but also to investigate their causes and consequences.

Late this spring, Alsalem released a report titled Sex-based violence against women and girls: new frontiers and emerging issues. The report is global in scope. It points out cases of gender-based violence in countries like Afghanistan, India, Myanmar, and Sudan that are egregious to Western sensibilities. But Alsalem doesn’t give Western countries a free pass. Sex-based violence happens here too. The most frequently mentioned Western countries in the report are Canada, the United Kingdom, and Israel.

Alsalem touches on many forms of sex-based violence in her report. We will touch on two that relate to the Let Kids Be campaign: gender ideology and medical transitioning for minors.

Gender ideology

Alsalem devotes more space to discussing the abandonment of biological sex in favour of gender ideology than any other issue. Canada is one of the worst culprits. In the space of five short years, the federal government and almost every single province and territory incorporated gender ideology into their human rights statutes. Prior to 2012, these statutes forbade discrimination based on sex. But between 2012-2017, they added gender identity and gender expression as prohibited grounds for discrimination. This has allowed men to compete in women’s sports, men to enter women’s private spaces, teaching gender ideology to school children, and a surge in medical transitioning for minors.

In response, Alsalem said this in a recent speech before the UN: “Let me be frank. I never imagined the day would come where my mandate would deem it necessary to prepare a report affirming that the words women and girls refer to distinct biological and legal categories.”

“Let me be frank. I never imagined the day would come where my mandate would deem it necessary to prepare a report affirming that the words women and girls refer to distinct biological and legal categories.”

– Special Rapporteur, Reem Alsalem

And thus, the report starts with a simple definition – or rather insisting – of terms:

“Sex” is understood as a biological category and as a distinction between women and men, as well as between boys and girls. References to “sex” refer to the biological distinction between males and females, characterized by divergent evolved reproductive pathways through which, all else being equal, males develop bodies oriented around the production of small gametes and females develop bodies oriented around the production of large gametes. As evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins notes: “Sex is a true binary.”

The term “gender”, on the other hand, has been defined by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women as the social meanings given to biological sex differences. It is supplementary to and built upon biological differences between women and men… In the last few decades, the term “gender” has wrongly been taken to be synonymous with the term “sex”, including in some international declarations and instruments.

The report ends with a simple recommendation: governments must “ensure that the terms ‘women’ and ‘girls’ are only used to describe biological females and that such a meaning is recognized in law… Legislation and policies that expand the definition of sex to include ‘certified’ or ‘legal’ sex or conflate sex with gender identity or substitute one term for the other should be rescinded.”

Medical Transitioning for Minors

Perhaps the greatest effect of replacing sex-based identity with gender-based identity is the exponential growth of medical transitioning for minors in Canada and other Western countries. Alsalem condemns medically transitioning minors in the strongest terms:

“The long-lasting and harmful consequences of social and medical transitioning of children, including girls, are being increasingly documented. They include: persistence or intensification of psychological distress; persistence of body dissatisfaction; infertility, early onset of the menopause and an increase in the risk of osteoporosis; sexual dysfunction; and loss of the ability to breastfeed in cases of breast mastectomy (to mention a few). That has rightly led several countries, such as Brazil, the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the United Kingdom to change course and restrict children’s access to puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones and surgery on sexual and reproductive organs. Allowing children access to such procedures not only violates their right to safety, security and freedom from violence, but also disregards their human right to the highest standards of health and goes against their best interests. Children are also not able to provide informed consent for such procedures. In situations in which such procedures have been found to have caused grave and lifelong harm, consent would be meaningless for both adults and children.”

Alsalem recommends that governments: